|

Matt's views on Rugby and

the professional era

As a young fellow growing up on the Far

North Coast of New South Wales I came under

the spell of Rugby through my Dad's association

with the Coffs Harbour Rugby Club: The Snappers!

It

was of course an amateur code then, a game

played for the love of it, not money. Rugby

is still largely dependent upon amateurism

for its survival as only the elite levels

of the game receive fiscal rewards for their

efforts on the paddock. However when I was

growing up Rugby was the great sporting

bastion of amateurism throughout the world.

Rural rugby clubs of today like yesteryear

remain, on the whole, amateur and they survive

and thrive because of the determination

of a bunch of people believing in the local

club. Coffs Harbour was and is no exception

to this rule. It

was of course an amateur code then, a game

played for the love of it, not money. Rugby

is still largely dependent upon amateurism

for its survival as only the elite levels

of the game receive fiscal rewards for their

efforts on the paddock. However when I was

growing up Rugby was the great sporting

bastion of amateurism throughout the world.

Rural rugby clubs of today like yesteryear

remain, on the whole, amateur and they survive

and thrive because of the determination

of a bunch of people believing in the local

club. Coffs Harbour was and is no exception

to this rule.

Having been around the Coffs Harbour Rugby

Club since I was a baby the red and black

of our strip was a familiar and comforting

sight. It stirred up a sense of allegiance

long before I really knew what the game

was all about. It has to be said that my

main sporting interest was cricket when

I was a boy. Around the age of ten to thirteen

cricket held a great deal more appeal and

in hindsight this was largely thanks to

television and the manner in which it made

the game particularly accessible to me,

as a spectator. Dad and I used to make a

trip once a year to the Sydney Cricket Ground,

and thanks to friends, we managed to get

seats in the Members and watch the Australian

First XI do battle with bat and ball. Then

as my tentative teenage years began I was

drawn to Rugby and watching more regularly

the efforts of the Club that Dad had coached

for ten years before he advanced onto take

charge of the NSW Country Team and later

the NSW B and NSW Rugby sides.

I regard myself as having had a very privileged

relationship with Rugby because of these

things. Especially when one considers the

fact that I have never played the game and

remained ensconced on the sidelines.

The Coffs Harbour Rugby Club allowed me

an opportunity to participate as an active

member and contributor to its fortunes by

asking me to be the Club's correspondent

for the local newspaper, The Coffs Harbour

Advocate. For three seasons, 1986 through

to 1988, I wrote the pre and post match

Rugby reports for the paper. It was a wonderful

experience for me because it enabled me

the opportunity to participate in the Club

and vicariously play at all levels. I wrote

about all the grades and recounted the hopes

for the approaching match, and the details

of the games played and as a consequence

I found a voice and opportunity that allowed

me to feel a part of the game.

Meanwhile, because Dad was coaching some

of the best players in Australian Rugby

at the time, I also had the opportunity

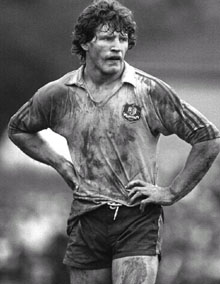

to meet some of these fellows. The first

of whom was Simon Poidevin. I met him at

the Sydney Cricket Ground after the Wallabies

had played the All Blacks in a one off test

in 1984. Dad had taken me into the dressing

sheds after the match and he pointed out

a player who had his back to me, who had

a great many sergeant stripes all over him

thanks to the stray boots of the All Black

pack. As an impressionable young fellow

I was struck by the strength and toughness

of Poidevin. I would later come to appreciate

him as a good man and fine player whose

uncompromising play would eventually be

rewarded in him being among the First XV

to win the Webb Ellis Trophy in 1991.

My

Rugby appreciation began then in the amateur

years and continued on during the tumultuous

dawning of the professional era to the present

day. And I had the good fortune of being

a spectator who enjoyed the thrills of the

local rugby club experience whilst also

seeing, meeting, knowing and vicariously

experiencing the highs and lows of those

at the heart of our national team. I have

been privileged enough to see the game played

the whole world over, and I have met and

conversed with some of great internationals. My

Rugby appreciation began then in the amateur

years and continued on during the tumultuous

dawning of the professional era to the present

day. And I had the good fortune of being

a spectator who enjoyed the thrills of the

local rugby club experience whilst also

seeing, meeting, knowing and vicariously

experiencing the highs and lows of those

at the heart of our national team. I have

been privileged enough to see the game played

the whole world over, and I have met and

conversed with some of great internationals.

Therefore in considering my views about

the professional era it is worth doing so

by taking the time to have a look at rugby

in a historical sense so that my opinions

and gut feelings are placed within the context

of time.

I will borrow heavily here from the text

in The Story of the Rugby World Cup, by

Nick Farr-Jones which I assisted him in

as a researcher.

Rugby is of course a game without borders,

played by people of all shapes, sizes, and

abilities and enjoyed by spectators and

followers just as diverse. From the balmy

islands in the Pacific to the chilling pitches

of northern Europe, across the expansive

landscape of southern Africa and within

the small municipality of Monte Carlo, you

will find a rugby club. There will be a

playing position and a home for the young

seven-year-old starting up in the touch

version of the game as there will be for

the seventy-year-old die-hard who still

thrills from running into sweaty bodies

even though the colour of his shorts precludes

him from being tackled.

The physical aspect of the game is often

uncompromising. It is a contact sport that

exacts its measure of punishment, but from

this there comes that sense of having done

one's bit that is known to all sports people.

Players will go hammer and tongs for eighty

minutes but once a game is over, rugby lore

deems that by-gones be by-gones as players

depart the pitch together and the usual

post-match festivities or third half, as

the French call it, commence. It is something

rugby players from the local clubhouse in

Maitland in rural Australia share with players

from other coal mining villages like Neath

in Wales. A rugby man from Waikato in New

Zealand might not speak French but given

half a chance he will have a great deal

in common with a player from Brive in France

Profond (deep France) once a rugby ball

is placed between them.

This traditional and international appeal

has allowed rugby to thrive ever since the

day the young schoolboy footballer, William

Webb Ellis, from Rugby School in England

decided, against the rules of his game,

to pick up the round ball, tuck it under

his arm and run with it. His defiant actions

became a hallmark for future combatants.

But with the tradition that quickly developed

there also came a reluctance to change.

The story of the Rugby World Cup is as much

about revolution as evolution and it tells

of those who dared to stand up to the traditionalists

and, like Webb Ellis, engender a sense of

innovation. By so doing, these visionaries

not only created one of sport's great events,

but also inadvertently gave rugby a sense

of strength and conviction that enabled

it to remain intact as the game shifted

from being a pleasure to a business, from

being an amateur pursuit to a professional

career.

Although

rugby was included in the modern Olympic

Games on four occasions it was dropped after

1924, the American Eagles being the last

team to win Olympic gold. For decades various

players and administrators from the four

corners of the world muttered about the

need for a global event. Unfortunately none

were in ultimate positions of authority. Although

rugby was included in the modern Olympic

Games on four occasions it was dropped after

1924, the American Eagles being the last

team to win Olympic gold. For decades various

players and administrators from the four

corners of the world muttered about the

need for a global event. Unfortunately none

were in ultimate positions of authority.

The traditional custodian of the game,

the International Rugby Board (IRB) was

controlled by the Home Unions: the English,

Welsh, Irish and Scottish Rugby Unions.

They were the founding fathers of the game

and were steadfastly opposed to any talk

of a world tournament, believing such an

event would pose a direct threat to the

amateur status of the game, the tenet upon

which rugby sought to distinguish itself

from other football codes. Determined to

kill off the concept of a world tournament,

the IRB passed a ruling in 1968 disallowing

any national rugby body to host any international

competition of the world cup type.

By the 1980s other member Unions were invited

to join their esteemed British colleagues

on the holy IRB. South Africa, France, New

Zealand and Australia now had their say

on the future running of the global game.

The overbearing conservatism of the four

Home Unions did not rest easily with the

new members and a power struggle ensued.

Without a Rugby World Cup tournament there

was constant conjecture as to which team

held the mantle of the world's best in any

given generation. The Home Unions and France

played each winter in the traditional 5

Nations tournament and the mighty All Blacks

clashed regularly against the Springboks

from South Africa. This was halted in the

early eighties following the signing of

the Gleneagles Agreement banishing South

Africa from the world stage until they got

their political house in order. And the

Wallabies each year played against the All

Blacks for the Bledisloe Cup. The debate

as to who was the best would intensify on

the marvellous occasions when teams from

opposing hemispheres clashed or the legendary

British Lions toured as they did every four

years.

Despite these intense battles, or possibly

because of them, a few believers remained

steadfast in the vision they harboured to

create a proper competition to determine

the world's best, a competition that would

also showcase rugby and further establish

its international credentials. While no

one man can be given the credit for thinking

up the Rugby World Cup concept, there are

a few individuals who are central to its

story.

Such a rugby revolution required men with

strong rugby pedigrees, of significant credibility,

political nous and above all possessing

strong wills. One such man was Sir Nicholas

Shehadie from Australia. He had played 30

tests for the Wallabies in a career that

lasted from 1947 to 1958, testimony in itself

to his playing ability and tenacity. He

was a big, uncompromising man, widely regarded

as the cornerstone of the Wallaby pack having

mixed his career between the front and second

row. He was a natural leader who would have

responsibility bestowed upon him without

seeking it and would go on to captain his

country with distinction. Shehadie was widely

respected, evidenced by being given the

rare honour of playing for the British Barbarians

against his own Wallabies in 1958.

Following his distinguished rugby career,

Shehadie turned his attention to business

and also became involved in local government,

going on to serve the city of Sydney as

Lord Mayor. He would later Chair a number

of organisations including the Sydney Cricket

Ground Trust and the television broadcaster

SBS. When he assumed the presidency of the

Australian Rugby Union (ARU) in 1980, Shehadie

was determined to create a Rugby World Cup

tournament.

The

need to bring about structural change to

the game increased in the early eighties

as rumours spread that players were being

offered vast sums of money to join a break-away

professional coup. Acting as the front man,

Australian journalist David Lord had reportedly

signed up a number of the leading players

and the urgency to protect the game increased.

Shehadie had observed the revolution in

Australia's summer sport some years earlier

when media magnate Kerry Packer had dramatically

illustrated how television and sport could

create gold when he stormed the cricket

world creating a rebel world series cricket

event. The

need to bring about structural change to

the game increased in the early eighties

as rumours spread that players were being

offered vast sums of money to join a break-away

professional coup. Acting as the front man,

Australian journalist David Lord had reportedly

signed up a number of the leading players

and the urgency to protect the game increased.

Shehadie had observed the revolution in

Australia's summer sport some years earlier

when media magnate Kerry Packer had dramatically

illustrated how television and sport could

create gold when he stormed the cricket

world creating a rebel world series cricket

event.

Shehadie flew to New Zealand to meet with

his Kiwi counterpart, Cec Blazey. There

was mutual respect and it was quickly agreed

that New Zealand administrator Dick Littlejohn

would team up with Sir Nicholas to convince

the IRB of the need for a Rugby World Cup

to maintain rugby's relevance and further

heighten its attraction to the participants

at the top level.

It was never going to be an easy task and

the two men faced significant resistance

from the member Home Unions opposed, as

always, to change. Shehadie recalls being

summonsed before the IRB in London in 1985

to defend his proposal. The Home Unions

were determined to quickly kill off any

radical change. But Shehadie and Littlejohn

would not back off and argued their case

whilst rebutting the claims that a global

event would tear at the very heart of the

game. Not that everyone in the room was

opposed to the concept, as the chairman

of the IRB that year was the affable Dr

Roger Vanderfield, a true believer in the

ideas being defended by his brave antipodean

brothers.

Finally it came to a vote. Without knowing

exactly how the numbers fell, some leaks

gave an insight into the positions adopted.

The South Africans abstained, as they no

doubt felt disinclined to commit to an event

they would not be invited to take part in.

The French, distrusting things British,

are believed to have voted for the plan.

Their administrative style can often be

compared to their playing style - daring,

exhilarating, sometimes frustrating, but

most often dramatic. For the Rugby World

Cup to get up, however, at least one of

the members from the Home Unions had to

break away. While it is unknown to this

day who that was, there is strong evidence

to suggest it was England who jumped ship

and made the vital break with the past.

The Rugby World Cup could now become a

reality and fittingly it was decided that

the inaugural event would be co-hosted by

Australia and New Zealand.

The

majestic Irish and British Lions winger

of the 1950s, Dr A J (Tony) O'Reilly said

of the Rugby World Cup that, 'For over 100

years the pleasures of rugby for players

and spectators were confined almost monastically

by region and by class, and now to echo

the words of W. B. Yeats, "All is changed,

changed utterly." The change agent has been

the Rugby World Cup and it is the nature

of this change that is so exercising and

so exciting. If the change is inclusive

and imaginative, it will improve the laws

and extend the horizons of the game. But

if it is narrow, defensive and crassly commercial

it will damage the soul of the game and

endanger the Corinthian values which have

captured the imagination of rugby people.'

There was much to look forward to. The

majestic Irish and British Lions winger

of the 1950s, Dr A J (Tony) O'Reilly said

of the Rugby World Cup that, 'For over 100

years the pleasures of rugby for players

and spectators were confined almost monastically

by region and by class, and now to echo

the words of W. B. Yeats, "All is changed,

changed utterly." The change agent has been

the Rugby World Cup and it is the nature

of this change that is so exercising and

so exciting. If the change is inclusive

and imaginative, it will improve the laws

and extend the horizons of the game. But

if it is narrow, defensive and crassly commercial

it will damage the soul of the game and

endanger the Corinthian values which have

captured the imagination of rugby people.'

There was much to look forward to.

It was perhaps ironic that within a decade

of the inaugural Rugby World Cup the code

at the top level turned professional. After

all it was the conservative British hierarchy

who had avoided the arrival of the global

event fearing it would professionalise the

code and ultimately change the fabric of

the sport.

But the pressure which drove this change

did not come from players demanding a slice

of the huge profits being generated from

the Rugby World Cup tournament, but rather

came from the fierce and acrimonious battle

between traditional rugby authorities and

the World Rugby Corporation (WRC).

The announcement of this professional revolution

was fittingly made in Paris. The southern

hemisphere nations had pushed hard for the

professional game. Their players had been

tempted by the big money being bandied about

by WRC together with Super League and they

had secured the ten-year money from News

Corporation for the Super 12 and Tri-Nations

series. As such it was not surprising that

the ARU, under former banker John O'Neill,

was well prepared for the start up of the

professional game. Recruited to head up

the ARU O'Neill brought with him the extensive

business skills required to manage the change

and ensure the books balanced after player

salaries had been paid.

But not everyone in rugby circles was happy

with the on-set of professional rugby. Little

funding seemed to end up at the traditional

grass roots. Rather the bulk of the New

Corporation funds seemed to disappear directly

into players' pockets particularly after

they threatened to sign WRC contracts. Smaller

rugby nations felt they would fall behind

without the support of their bigger brothers.

They were not a part of the lucrative Tri-Nations

or in the north Six Nations championships

and could not afford to pay their players.

Forced to remain amateur, it was inevitable

that they would lose their leading players

who would go abroad in search of the all-important

contract. In such a climate the gap between

the big and the small was bound to widen.

The

players soon discovered that normal or day

jobs would have to be sacrificed as they

were now 100 per cent accountable to their

new employers and would be on call throughout

the day. This manifested itself in a new

mind set as players accepted whatever administrative

decisions were thrust upon them. Nick Farr-Jones

recounts the story from when he was newly

appointed the Wallaby captain Back in 1988,

when for the first time the ARU had negotiated

the logo of a Japanese communications company

to appear on the jersey. Nick and the team

had not been consulted and as players who

still pulled on the jersey for the love

and honour and not the money Nick as the

new captain, had angrily confronted the

President Joe French, insisting this could

not happen without the players' consent.

As Nick saw it he and the team were the

ones who were accountable to past Wallaby

traditions. The upshot was that the logo

disappeared. In 1997 however the ARU at

the behest of its new sponsor Reebok, paraded

a totally new jersey that was correctly

described by Peter FitzSimons as looking

like 'volcano vomit on a rag…where there

used to be a kind of holy sheen, there is

now a commercial catastrophe.' The players,

well aware of where the money was coming

from to pay their lucrative contracts, were

incapable of objecting and irrespective

of their inner thoughts went along for the

ride. The

players soon discovered that normal or day

jobs would have to be sacrificed as they

were now 100 per cent accountable to their

new employers and would be on call throughout

the day. This manifested itself in a new

mind set as players accepted whatever administrative

decisions were thrust upon them. Nick Farr-Jones

recounts the story from when he was newly

appointed the Wallaby captain Back in 1988,

when for the first time the ARU had negotiated

the logo of a Japanese communications company

to appear on the jersey. Nick and the team

had not been consulted and as players who

still pulled on the jersey for the love

and honour and not the money Nick as the

new captain, had angrily confronted the

President Joe French, insisting this could

not happen without the players' consent.

As Nick saw it he and the team were the

ones who were accountable to past Wallaby

traditions. The upshot was that the logo

disappeared. In 1997 however the ARU at

the behest of its new sponsor Reebok, paraded

a totally new jersey that was correctly

described by Peter FitzSimons as looking

like 'volcano vomit on a rag…where there

used to be a kind of holy sheen, there is

now a commercial catastrophe.' The players,

well aware of where the money was coming

from to pay their lucrative contracts, were

incapable of objecting and irrespective

of their inner thoughts went along for the

ride.

The first two years of professionalism

were turbulent. Michael Lynagh retired at

the end of the 1995 Rugby World Cup and

Phil Kearns took over the job. He then suffered

from injuries and his part in the professional

negotiations and was replaced by John Eales

as Captain. The team struggled to find the

rhythm it had enjoyed in previous years

and coach Greg Smith battled on in unenviable

circumstances during a period of time that

looked as if it was the same as before,

but which was incredibly different. None

of the familiar landmarks really existed

as they had and players, coaches, administrators

and as a consequence spectators struggled

to comprehend what was really happening.

It is within the context of these changes

that I felt a shift in my own appreciation

for the game once it became professional.

Obviously as a young man I was spoilt through

my aforementioned associations with the

game. I had come to know some of the best

players in the world and I have always believed

that it in part amateurism provided the

opportunities for that to take place. It

is no coincidence that once the professional

era began many of those whom I had known

personally to wear the green and gold had

mostly retired. One fellow who had not was

Phil Kearns, the great Wallaby hooker, and

his last years in Rugby parallel my own

relationship with the game.

During his period of injury and banishment

my allegiance to the great game had waned.

I still enjoyed watching New South Wales

play, and I went to Test matches and heartily

supported our national team but a particular

disenchantment had set in. Partly it was

due to the understanding that the sport

had become less significant in my life.

I suppose this was initially inevitable,

as the needs of creating a career and finding

an independent life meant others things

became a priority. And of course in seeing

my friends and connections retire from the

game my emotional ties were no longer as

strong.

Professionalism

had introduced a controversy of its own

to the game, and sullied its reputation

it seemed to me. A tone of individual self

interest had crept into the vernacular where

before the team and national interest had

been the tenant upon which all others things

depended. It no longer felt like my game,

which was a churlish attitude in hindsight,

but one I felt keenly. Professionalism

had introduced a controversy of its own

to the game, and sullied its reputation

it seemed to me. A tone of individual self

interest had crept into the vernacular where

before the team and national interest had

been the tenant upon which all others things

depended. It no longer felt like my game,

which was a churlish attitude in hindsight,

but one I felt keenly.

However, this loss of interest was not

due to the fact that the Wallabies were

not necessarily performing as well as they

had in recent years. In fact I bristled

when supporters would dismissively declare

the team's efforts as hopeless whenever

they failed to win, or in fact won but not

by a margin that was expected.

Unlike a great many Johnny Come-Latelys

to the game I had followed the fortunes

of the Australian Rugby team in the early

and mid eighties and painfully witnessed

the All Blacks defeat us from any where

between one point to twenty. I never underestimated

what it took to beat any of the Home Unions

either at home or abroad. I had grown up

on a diet of Rugby folklore wonderfully

presented by the likes of Peter Fenton's

The Running Game so I knew victories were

few and far between for our small playing

nation in the past. I had stood in despair

with others to see Serge Blanco score in

the corner of Concord Oval for France to

bundle us out of the Inaugural Rugby World

Cup semi final. I had suffered the ignominy

of attending Bledisloe Cup Test matches

at the Sydney Cricket Ground, Concord Oval

and the Sydney Football Stadium as an Australian

supporter only to find that there were more

people wearing black and flying the silver

fern than our own green and gold, even when

the match was played in our country!

But it was during the season of 1998 and

1999 that I again found some of my interest

and passion of before enlivened. It was

obvious to me in particular on the evening

that I went out to watch the Wallabies play

the All Blacks at Stadium Australia in 1999

in what was their last match before heading

to Wales for the Rugby World Cup.

I was more excited about that particular

match than I had been in years. I had even

placed 20 dollars on the boys for a win

at odds of 8:1.

On paper it seemed we were doomed to lose.

Stephen Larkham and John Eales were injured

and could not play; Rod Kafer was belatedly

slotted into the pivot's role. The All Blacks

were getting stronger and stronger, they

had beaten us in the slush of New Zealand

and they were headed towards the Rugby World

Cup with the aura of favourites wrapped

tightly about them. However, I had a sixth

sense that this was actually going to be

our night and when the players arrived to

belt out the National Anthem the new stadium

shook.

From

the moment the Wallabies assembled to face

the All Blacks and their haka I searched

for the figure of Phil Kearns, and I smiled

inwardly when I saw him. Kearns was standing,

as always, not so far away from the shouting

All Blacks, bearing a facial expression

that suggested he was bemused by the antics,

but which you knew was masking a fierce

determination to get on top of his old nemesis

yet again. He was wearing the Number 2 for

the last time on Australian soil. He had

previously announced this would be his last

year of Rugby after having played for the

last decade with a tenacity that was matched

by ability and commitment in the toughest

combatant position on a Rugby paddock. And

it was a moment of some significance even

for me. From

the moment the Wallabies assembled to face

the All Blacks and their haka I searched

for the figure of Phil Kearns, and I smiled

inwardly when I saw him. Kearns was standing,

as always, not so far away from the shouting

All Blacks, bearing a facial expression

that suggested he was bemused by the antics,

but which you knew was masking a fierce

determination to get on top of his old nemesis

yet again. He was wearing the Number 2 for

the last time on Australian soil. He had

previously announced this would be his last

year of Rugby after having played for the

last decade with a tenacity that was matched

by ability and commitment in the toughest

combatant position on a Rugby paddock. And

it was a moment of some significance even

for me.

I had met Kearns in 1989 or 1990 after

Bob Dwyer had picked him from obscurity

to tackle the Kiwis on the Wallaby tour

of New Zealand of '89. He was then and remained

a friendly fellow who never seemed to busy

to say hello and share a word or three if

we ever came across each other. In the years

between his first Test and this, his last

in Australia, Kearns had experienced the

immeasurable highs and lows of Rugby. He

had been a member of the 1991 victorious

Rugby World Cup Wallaby side and had enjoyed

victories over the South African and All

Black Rugby sides in historical encounters.

Kearns had known the best of the amateur

days and the worst of professionalism. Having

been captain of his national side at a time

when the media barons made a move on the

game professionally to own and exploit the

sport Kearns was one of those men who found

themselves placed in a position of decision

making for which they had never applied.

And then he suffered the ignominy of a crippling

injury to his Achilles' heel that all but

threatened to kill dead his Rugby career.

However, demonstrating a physical and mental

toughness he over came the worst of days

to enjoy once more the best of days. In

much the same way that Tim Horan demonstrated

an incredible single mindedness to look

beyond his awful knee injury and to return

to the world stage as the greatest player

of the 1999 Rugby World Cup so did Kearns

manage a rehabilitation that is a testimony

to any man or woman coming back from injury.

On this night that Kearns took on the Kiwis

I realised that he was the last Wallaby

of that era of Rugby I had been fortunate

enough to know intimately. He was the link

with my immediate past, when Nick, Simon

and Steve Cutler and Peter FitzSimons had

been around and so it was of a powerfully

personal moment to be there. As the All

Blacks completed their war cry and wandered

to their positions for the kick off, the

adrenalin not only poured through their

veins, but mine as well. There was an expectation

in the air that this was going to be special

and from the moment that the kick off was

taken it was a match of gladiatorial proportions.

When Australia emerged at the end of a

torrid eighty minutes emphatic victors I

was about the happiest I that have ever

been at a Rugby Test. It was the stuff of

legend and the team had proven itself in

a way that would only be surpassed by their

victories in the Rugby World Cup final,

and against the British and Irish Lions

and in the Tri Nations in the following

years. It was a victory and display that

won me over to the professional era and

I waited until the very last so that I could

watch Kearns walk around the field, holding

the Bledisloe Cup and lapping up the spectators

cheers. It was a terrific moment and although

Kearns would be cruelly robbed of the opportunity

to lift the Webb Ellis Trophy through injury

once again, his part in the transition was

completed on a positive note. And that was

enough for me to restore my faith in the

game.

The

success of the 1999 Rugby World Cup campaign

for the Wallabies presented me with a very

real appreciation as a spectator for the

way in which professionalism could work.

Rod MacQueen had brought about a structure

to the business plan and fostered a re-identification

with the historic principles of being a

Wallaby, both on and off the paddock. Blessed

with men like Horan, Kearns, Matt Bourke,

George Gregan and Eales Rod MacQueen had

players that appreciated that there is a

need to give something to the game's name

and that the currency of choice for its

support base was not the dollar. The fact

that Bob Templeton was the Assistant Coach

was undoubtedly a contributing factor to

this shift. The

success of the 1999 Rugby World Cup campaign

for the Wallabies presented me with a very

real appreciation as a spectator for the

way in which professionalism could work.

Rod MacQueen had brought about a structure

to the business plan and fostered a re-identification

with the historic principles of being a

Wallaby, both on and off the paddock. Blessed

with men like Horan, Kearns, Matt Bourke,

George Gregan and Eales Rod MacQueen had

players that appreciated that there is a

need to give something to the game's name

and that the currency of choice for its

support base was not the dollar. The fact

that Bob Templeton was the Assistant Coach

was undoubtedly a contributing factor to

this shift.

Therefore I regard professionalism now

as something that is working well and if

managed correctly on a provincial and global

scale the game and its people will benefit

greatly from it. Of course had Rugby not

turned professional our game would have

been plundered by the league. It is a testimony

to all involved that it largely held itself

together on the international scene. What

has yet to be shown is that the powerful,

wealthy nations are in a position to look

after the minnows and whether club franchises,

as they exist in England, will become increasingly

powerful to the detriment of the international

calendar.

back

to the top of the page

back to Rugby

|